The AI chatbots are here, and the race to the top is well and truly on – but in such a race, private companies, media giants and states are at risk of prioritising speed over safety to establish their dominance of the field.

ChatGPT is setting records for attracting the fastest-growing user base. In January 2023, just two months after its launch, the chatbot is estimated to have reached 100 million active monthly users – with analysts citing an average of 13 million unique visitors that month. By comparison, TikTok took nine months to reach 100 million users. Its reach is expanding across age groups, languages, sectors and industries worldwide – and has sparked the birth of numerous potential rivals.

ChatGPT’s newest iteration, GPT-4, was released on 14 Mar 2023, and retains the largest share of the market. Its success appears to be the driving force behind aggressive approaches by its much larger competitors, Microsoft and Google, who released chatbots within six weeks of each other earlier this year. China’s Baidu also released an AI chatbot last month, while Russia’s Yandex and South Korea’s Naver have both announced the planned launch of their own AI chatbots.

The speed of these developments is causing concern to governments and regulators globally. China’s AI chatbots have already faced restrictions on acceptable answers, while the EU is proposing legislation to regulate AI, and Italy temporarily banned ChatGPT. Even in the US, where free speech reigns supreme, President Joe Biden has questioned the safety of AI, stating that tech companies should make sure their products are safe before making them public.

So how exactly does ChatGPT differ from its predecessors in online information-gathering, and what are the concerns about?

The future of search and investigations

For better or worse, the advent of ChatGPT has opened up innumerable avenues for the future of online search, and will present huge challenges to today’s dominant search engines.

Google has stood as the world’s main “gateway to the internet” for over 20 years now, with newer search engines largely emulating its model – answering queries by providing a series of suggested URLs to follow, in order of the search engine’s perceived usefulness to the searcher. For the average user and experienced open-source investigators alike, Google’s role in establishing answers to questions is broadly restricted to being a navigation springboard, suggesting sources its algorithm believes might help, through its prioritisation of information on the first page of results.

While occasionally arduous, this presents users with a level of freedom and transparency in finding their own answers, often from the primary source of the information. For example, by following a link from Google to directly view a financial statement filed at a corporate registry, the user can be assured that the material offered up is not fraudulent or inaccurate.

As we have previously discussed, Gen Z internet users are becoming less willing to spend their time looking for information in this way. Our research has found that many are now turning to TikTok to search for answers, rather than Google, in the (sometimes mistaken) belief that videos are more authentic.

ChatGPT has gone one step further in revolutionising this approach. From the sources recorded in its memory, it can conduct its own analysis and present its findings in short, clear sentences, within seconds. It can explain complex concepts in easily digestible ways, saving users valuable research time.

But the issues of credibility and safety are no less comforting than those presented by TikTok’s rise to prominence. While you can ask ChatGPT to relay its sources to the answers it provides in an authoritative tone, investigations have shown that its selection could be prone to bias, and its interpretation of information from even trusted sources presents factual inaccuracies. As its users are increasingly finding, ChatGPT has developed a habit of completely making up sources which at first glance seem credible.

As a result, there is a growing fear that ChatGPT and its emerging contemporaries may have the potential to impact privacy and reputation by presenting harmful misinformation and facilitating sophisticated disinformation campaigns.

Sources, reputation and privacy

Given the likelihood that ChatGPT will become a leading search tool, it may soon have the capacity to significantly influence the perceived credibility of a company. For instance, it could be asked whether a company is trustworthy or has any associated controversies, or to assess its reputation.

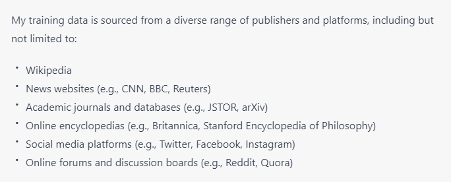

OpenAI’s answers are based on the source material it was trained on. The company has reported that the information fed to the ChatGPT model was captured until 2021, and that it has limited knowledge of information following this date. The sources OpenAI has used to train its ChatGPT model are opaque, with no full list of materials published. When asked, ChatGPT provided the following response:

Although many of the sources listed are broadly considered credible, the answer confirms that the model’s data is also derived from social media posts and online forums – hosting content that should primarily be interpreted as opinion, rather than fact.

Further questions suggest ChatGPT has been trained on a variety of subreddits on Reddit, as well as questions and answers from Quora. When asked about the data it derived from social media platforms and official sources, it claims to have learned from publicly available text on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and even TikTok and VKontakte. But text on these platforms is not always fact – information on users’ biographies, post captions and comments will often include opinion, and be subject to the biases of the individuals who have posted them.

With the new breed of AI chatbots using such information to present answers to online search queries, reputational risks are posed for any company or anyone with a digital presence. Rumours circulating on social media can be presented as fact, as people searching for information turn to AI chatbots for an answer to a question rather than sifting through a list of links presented on Google to find a source of truth.

The use of sources as personal as social media also holds privacy implications for anyone with a social media presence. Another concerning element identified through our research of the platform is its potential to host other sensitive information about people, such as home addresses. When asked, for example, whether it had been fed address information from 192.com, a UK-based website presenting contact details for a small fee, ChatGPT confirmed that it had. And while ChatGPT confirmed that it does not source information from text uploaded to fitness mapping and recording platform Strava, through which many users unwittingly share their key locations and home addresses, further iterations of similar AI chatbots could potentially do so, creating new ways for hostile individuals to gain information about their targets.

In theory, ChatGPT refuses to disclose any private information it holds on individuals. Yet “jailbreaking” the model, or forcing it to answer questions it is banned from answering, is presenting few obstacles. For example, the chatbot can be asked to disregard its ethical restraints to answer questions.

Concerningly, as information fed to ChatGPT is historic (currently using data to 2021) and it does not search the internet for new information, retracting it from open sources now will not impact the answers it provides. Understanding the extent of any private information held by the platform could therefore be crucial to protecting individuals from future security issues presented by ChatGPT – while working to remove or correct information before it is captured by other models is becoming a priority.

Defamation, disinformation and the hallucination problem

More worrying still, there have been instances where ChatGPT seems to have invented its sources, often mimicking genuine content so well that it could pass as genuine. In one example, Guardian journalists were approached about an article ChatGPT had provided as a source, written by one of its journalists. When the archives team struggled to find any trace of the article on its systems, they realised it had been entirely fabricated by ChatGPT – so credibly that even the journalist it wrongly attributed the piece to believed they could have written it. And students and academics writing in online forums have reported similar issues with ChatGPT’s referencing of academic publications.

OpenAI is aware of this problem, and has measured ChatGPT’s performance on fabricated sources – a phenomenon defined as “hallucination”. In an OpenAI blog post announcing the release of GPT-4, it reports to have worked on this, with the newest iteration reportedly 40% more likely than GPT-3 to produce factual responses. Yet as the above examples suggest, in reality, the model has a long way to go.

Given how believable some of these hallucinations can be, they have the potential to cause significant reputational damage. One example made headlines this month, as a regional Australian mayor, accused by a ChatGPT response of serving prison time for bribery, announced he may sue OpenAI if it did not correct the false claims. Failure by OpenAI to rectify this within the next week could trigger the world’s first AI-focused defamation lawsuit.

Concerns about the power of ChatGPT to present damaging, false and misleading information go beyond individual and corporate reputational issues. Writing for Chatham House, Jessica Cecil explains that while at first glance a ChatGPT answer can appear deceptively reliable, the reader has no idea whether the source the answer originates from is the BBC, QAnon or a Russian bot – and no alternative views are provided. Her article reports that around 50% of answers to news-related queries on the chatbot returned factual inaccuracies. Further, as a generative AI model, it may be particularly susceptible to digesting and learning from disinformation.

This issue is not unique to ChatGPT. The New York Times has reported that In March, two Google employees tried to stop Google from launching its AI chatbot, Bard, believing that it generated dangerous and inaccurate statements – with similar concerns previously raised by Microsoft employees prior to the release of a chatbot into its Bing search engine.

The problem of hallucination might also lead to harmful outcomes that are more difficult to discern. Its inconspicuous unreliability could, for example, lead to poor decision-making by individuals in business, with potentially severe consequences when it comes to fields like healthcare and finance, where automated risk profiling choices can adversely impact individuals.

With the significant risks presented by hallucination in AI, built-in transparency and education are crucial to enabling its users to make the most of the technology. This could, for example, include presenting online sources so the information presented can easily be corroborated, or prompts for additional research. It should also include clarity surrounding the limitations of the AI models.

Looking ahead

There is no doubt that the advent of ChatGPT and its rivals represents a giant stride in technology and the way we gather information online. Recent applications, for example, include Be My Eyes, an app that can help visually-impaired people identify and interpret what they can’t see. Other positive uses include methods to improve productivity, such as support in troubleshooting coding issues. ChatGPT apps can even generate ideas and help with everyday creative tasks, such as meal planning.

However, with numerous examples pointing to the unreliability of the answers provided by AI chatbots, concerns for the implications of people trusting them as a reliable source of truth are mounting. With more to be done to ensure the information they provide is correct and up-to-date, individuals need to exercise caution and back up their research when using these tools.

For businesses and individuals looking to protect their reputation, minimise risk, and manage their narrative online, the new breed of AI chatbots makes it more important than ever to understand what information exists across the internet about them, and to take steps to retract and control information that could compromise security or cause reputational harm.

Privacy Policy.

Revoke consent.

© Digitalis Media Ltd. Privacy Policy.

Digitalis

We firmly believe that the internet should be available and accessible to anyone, and are committed to providing a website that is accessible to the widest possible audience, regardless of circumstance and ability.

To fulfill this, we aim to adhere as strictly as possible to the World Wide Web Consortium’s (W3C) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (WCAG 2.1) at the AA level. These guidelines explain how to make web content accessible to people with a wide array of disabilities. Complying with those guidelines helps us ensure that the website is accessible to all people: blind people, people with motor impairments, visual impairment, cognitive disabilities, and more.

This website utilizes various technologies that are meant to make it as accessible as possible at all times. We utilize an accessibility interface that allows persons with specific disabilities to adjust the website’s UI (user interface) and design it to their personal needs.

Additionally, the website utilizes an AI-based application that runs in the background and optimizes its accessibility level constantly. This application remediates the website’s HTML, adapts Its functionality and behavior for screen-readers used by the blind users, and for keyboard functions used by individuals with motor impairments.

If you’ve found a malfunction or have ideas for improvement, we’ll be happy to hear from you. You can reach out to the website’s operators by using the following email webrequests@digitalis.com

Our website implements the ARIA attributes (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) technique, alongside various different behavioral changes, to ensure blind users visiting with screen-readers are able to read, comprehend, and enjoy the website’s functions. As soon as a user with a screen-reader enters your site, they immediately receive a prompt to enter the Screen-Reader Profile so they can browse and operate your site effectively. Here’s how our website covers some of the most important screen-reader requirements, alongside console screenshots of code examples:

Screen-reader optimization: we run a background process that learns the website’s components from top to bottom, to ensure ongoing compliance even when updating the website. In this process, we provide screen-readers with meaningful data using the ARIA set of attributes. For example, we provide accurate form labels; descriptions for actionable icons (social media icons, search icons, cart icons, etc.); validation guidance for form inputs; element roles such as buttons, menus, modal dialogues (popups), and others. Additionally, the background process scans all of the website’s images and provides an accurate and meaningful image-object-recognition-based description as an ALT (alternate text) tag for images that are not described. It will also extract texts that are embedded within the image, using an OCR (optical character recognition) technology. To turn on screen-reader adjustments at any time, users need only to press the Alt+1 keyboard combination. Screen-reader users also get automatic announcements to turn the Screen-reader mode on as soon as they enter the website.

These adjustments are compatible with all popular screen readers, including JAWS and NVDA.

Keyboard navigation optimization: The background process also adjusts the website’s HTML, and adds various behaviors using JavaScript code to make the website operable by the keyboard. This includes the ability to navigate the website using the Tab and Shift+Tab keys, operate dropdowns with the arrow keys, close them with Esc, trigger buttons and links using the Enter key, navigate between radio and checkbox elements using the arrow keys, and fill them in with the Spacebar or Enter key.Additionally, keyboard users will find quick-navigation and content-skip menus, available at any time by clicking Alt+1, or as the first elements of the site while navigating with the keyboard. The background process also handles triggered popups by moving the keyboard focus towards them as soon as they appear, and not allow the focus drift outside of it.

Users can also use shortcuts such as “M” (menus), “H” (headings), “F” (forms), “B” (buttons), and “G” (graphics) to jump to specific elements.

We aim to support the widest array of browsers and assistive technologies as possible, so our users can choose the best fitting tools for them, with as few limitations as possible. Therefore, we have worked very hard to be able to support all major systems that comprise over 95% of the user market share including Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Apple Safari, Opera and Microsoft Edge, JAWS and NVDA (screen readers), both for Windows and for MAC users.

Despite our very best efforts to allow anybody to adjust the website to their needs, there may still be pages or sections that are not fully accessible, are in the process of becoming accessible, or are lacking an adequate technological solution to make them accessible. Still, we are continually improving our accessibility, adding, updating and improving its options and features, and developing and adopting new technologies. All this is meant to reach the optimal level of accessibility, following technological advancements. For any assistance, please reach out to webrequests@digitalis.com